"Daybreak is set in a fictional world in which all the world's major powers agree that climate change is fact."

This is how Daybreak was first introduced to me when I got to play it at a recent Gaming The System evening. It's easy to then think that's the hard part over and done with, but oh boy does Daybreak still manage to throw up a juicy challenge.

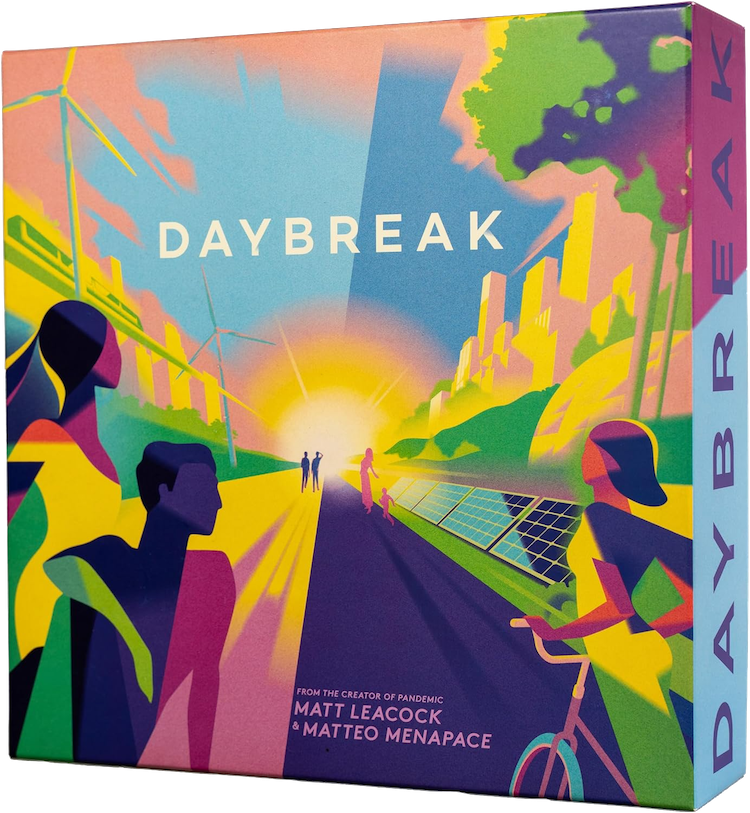

Designed by table top heavy weight Matt Leacock (Pandemic, Forbidden Island, and many others) and Matteo Menapace, in Daybreak 1-4 players take the roles of dominant world powers such as the USA, China, Europe, and somewhat confusingly, the rest of the world, in an attempt to reverse the course of climate change to avert catastrophe.

This is achieved by drawing cards to create a tableau in front of you that acts as an engine to reduce the carbon footprint of your nation, while keeping up with the energy demands by switching to green energy. This is only half of the challenge, however, as you will also need to invest in carbon capture strategies to ensure that any carbon that is released is captured before it can build up and create serious problems down the line.

Aside from working on your own tableau/engine, known as local projects, you can also work together to attempt to achieve global projects at the cost of cards. These global projects are powerful buffs that can help your local projects achieve their aims. For example, in the game we played, one of the global projects we invested in allowed us to double the clean energy output from any nuclear power plants in our tableau. Each round, the energy demands on your nation increases by a set amount so having a reliable source of green energy is very important.

The game is played over 6 rounds in which crisis cards are added to the map, global projects are started, then players complete local projects by drawing and placing cards, emissions are then added to the map board based on each players current carbon footprint, which are then either absorbed through the carbon capture initiatives or go into the thermometer track, gradually raising the temperature of the planet and increasing the number of crisis cards drawn each turn. Following all this any unresolved crisis cards are resolved. These crisis cards have devastating effects on the players' nations and can cause community crises, which if left to build up can cost the game. Much like the global initiatives, players can sacrifice cards to combat the crisis cards in an attempt to mitigate the impending disasters.

As cooperative games go, this game is highly cooperative. While each player has their own nation to worry about and their own engine to build, without sufficient communication and teamwork, the state of the global map can quickly go from bad to worse, which, incidentally is what happened to us. Those crisis cards are no joke and it's easy to forget about them while trying to shift your nation from dirty to clean energy while keeping up with the ever increasing demand.

Aside from the general structure of each round, there is no turn order when it comes to the main part of the game, in which players draw cards and decide whether to invest them in local initiatives, global initiatives, or use them to counter the disasters on the horizon. This creates a perfect forum for discussion, debate, and collaboration in which players really feel like world leaders sat around a table trying to work together to solve a problem. Each card is played with consideration as to how it can not only help you home nation but also the goals of the wider world (at least that's how it's supposed to work, I must confess I spent most of my cards rather selfishly on my local projects to the detriment of the global issues. But, hey, I know for next time).

Despite it's difficulty, this is a tremendously optimistic game that allows us to imagine a future in which world leaders can work together for the good of the planet. While challenging, the solution is always within sight. The game exudes the belief that with a few smart decisions and enough cooperation, we can find out way out of the present climate crises we find ourselves in. This optimism is evident in the colourful, uplifting art style that speaks of a bright future rather than the dingy, polluted present. Each card is carefully illustrated with bold colours and clear lines. On the whole the game is a joy to look at. Even the name, Daybreak, inspires visions of a utopian future.

As an excellent touch, each card contains a QR code (kids love QR codes) which can be scanned to learn more about the local projects they represent, such as Dirty Electricity Phase Out or Climate Debt Reparations. Everything about this game feels like it is trying to educate about the environment with the hope of instigating change, rather than succumbing to the bleak misery that is all too easy to fall into when viewing the world today.

Despite all this optimism, though, we cannot ignore the point I made at the beginning of this review. In Daybreak it feels as though the hard part has already been done. This is a present in which we've already achieved the fantastical in getting world leaders to cooperate and communicate. The game makes the statement that if we can just manage this, then a solution is in sight, but this is a a tremendously big If.

Overall, Daybreak is a joy to play and I look forward to getting to play it again. It strikes a good balance of being almost overwhelming while also dangling the carrot of success in front of you each round. I often find games that have no specific turn order can feel somewhat disorganised and chaotic but it avoids this and really does allow space for effective cooperative play. The game marries the mechanics and theme very well to create an intuitive and enjoyable experience that offers a satisfying challenge.

While I wouldn't recommend this game to those very new to the hobby, it is definitely one of the more accessible games to tackle a Big Issue like climate change, so if you want something to really get your teeth into with a terrific message, look no further than Daybreak.

If you are interested in joining in with Gaming the System, they meet twice a month at The Long Rest in Canterbury from 18:30 to 21:30 every 2nd and 4th Wednesday of the month. Gaming the System are a group interested in how board games can improve our understanding of the inequalities in the world and what we might do about them. They play games that challenge our understanding, help us to cooperate, and point towards new ways of dealing with the world. All the games available at their events are considered political (with a lower case p) in that they demonstrate certain morals and values and can open up wider political discussion.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment